two comedians

In the last canvas Edward Hopper ever painted, two clowns, one woman and one man, stand beside each other on the edge of a precipice. We view Two Comedians from right below that edge, the clowns’ feet just barely obscured by the lip of a stage deck that resembles a parapet. His right hand grasps her left at waist height, joining them into a single shape. Their free arms bend at the elbow, his left hand reaching across his torso to cradle his ribs upward in a protective gesture and her right hand stretching slightly forward at her chest, palm cupped and facing upward in an offering to no one. Their knees bend slightly, and their torsos push forward with the same degree of subtlety, their potential energy mounting skyward. A dark blue void stretches behind them, seemingly interminable in depth, interrupted on the left side of the canvas by the painting’s frame and, on the right, by the suggestion of a green hedge and the very edge of a proscenium that reads, as it meets the front of the stage deck below their four feet, like a frame within the frame. The comedians’ eyes are black voids, completely solid beneath foreheads devoid of eyebrows. The shade of red that colors the woman’s cheeks and lips is sinister; whatever she might be presenting with her left hand, whatever destination her come-hither motion might lead to, is menacing. They look, maybe, like they’re taking a bow.

Hopper, we know, was fascinated by the theater. He used its physical setting as subject matter and its inventiveness, its ability to conjure other realities from the same materials that make up our own, as an approach. In a few of his paintings (Soir Bleu, Rooms by the Sea), Hopper employs theatrical artifice to spur the mysterious and uncontrollable partner of any artwork: the imagination of the viewer.

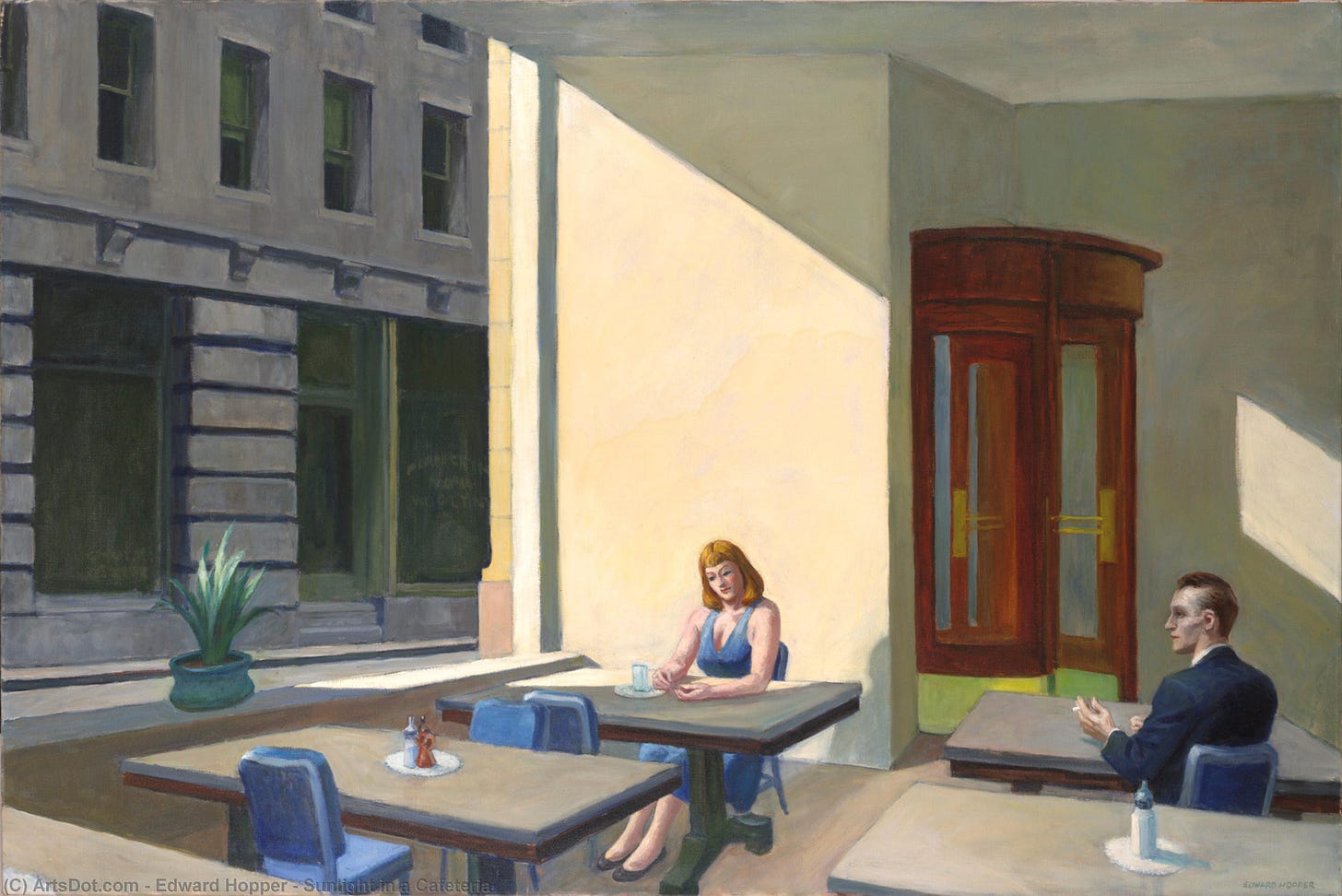

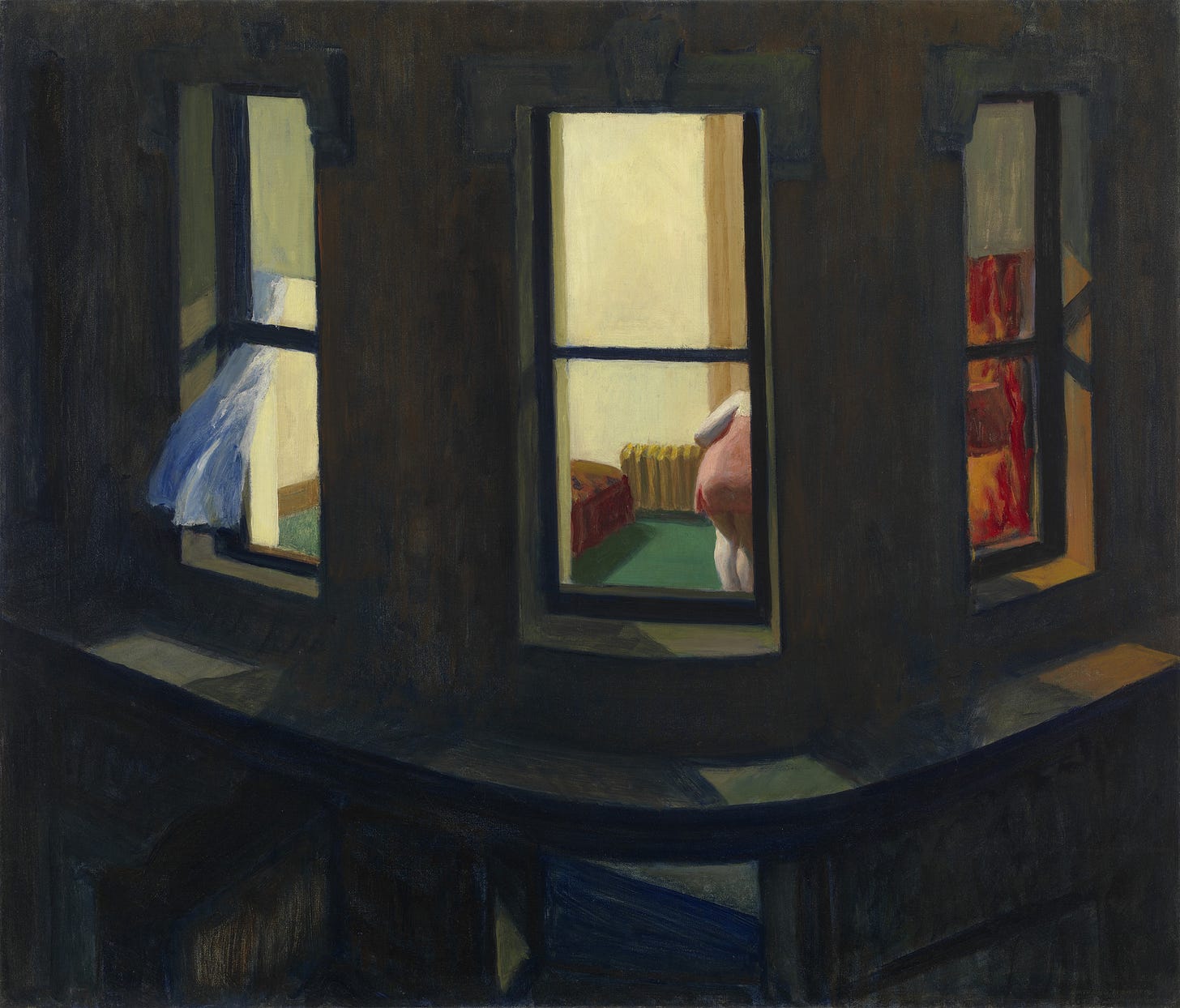

Viewing these canvases is liberating; they are an invitation to see where our own mind might take us. But for the most part, Hopper wielded artifice much less generously. Many of his paintings are stage sets: of a contrived city scene (Sunlight in a Cafeteria), of an interior–cum–still life (Room in Brooklyn), of a stint of voyeurism (Night Windows). The departure point, familiar scenes of everyday urban life, is still the same, but here, it is not generative. It is something to be reined in, doctored, and, ultimately, stifled.

I understand the impulse. Hopper found himself in a city that was constantly changing in ways he didn’t like and in a marriage that was less than happy, armed with a vocation that allowed him to alter reality and enough talent to do it believably, if only momentarily. His canvases are escape fantasies masquerading as candid portraits—we’d be forgiven, and so would he, for falling for the illusion.

But, then, Two Comedians. After a lifetime of artifice, they reach the end of the show. They stand on the edge. They look, maybe, like they’re taking a bow. They look, more so, like they’re about to jump.